Last month I wrote about the work of William Easterly, formerly of the World Bank, and noted authority on aid matters. He is a critic of the traditional approach to aid as he believes the top down approach betrays an arrogance that underpins its frequent failure.

Last month I wrote about the work of William Easterly, formerly of the World Bank, and noted authority on aid matters. He is a critic of the traditional approach to aid as he believes the top down approach betrays an arrogance that underpins its frequent failure.

He regards this approach as typical of ‘planners’. Planners think they have all of the answers already, and therefore tend to place their trust in external expertise and look for solutions from within their existing field of knowledge. Planners tend to favor top down solutions to each problem.

Searchers, on the other hand, readily admit that they don’t have the solution beforehand and accept that most situations are incredibly complex and require a very nuanced solution. Whereas planners like top down solutions, searchers tend to prefer bottom up ones instead.

The response to Ebola

One of the more prominent aid responses of recent times has been to the Ebola outbreak in west Africa. That response, led by the World Health Organization (WHO), has been analyzed recently by Medecins Sans Frontieres (MSF), and the results are not a good indication that any lessons have been learned since Easterly published his book 8 years ago.

“The Ebola outbreak has often been described as a perfect storm: a cross-border epidemic in countries with weak public health systems that had never seen Ebola before,” MSF said.

“Yet this is too convenient an explanation. For the Ebola outbreak to spiral this far out of control required many institutions to fail. And they did, with tragic and avoidable consequences.”

The head of the UN’s Ebola Mission even went as far as to brand the response as arrogant and not doing enough to engage with local communities in response to the outbreak.

This analysis was shared by a second report into the outbreak that was equally scathing.

“Had (the WHO and the United Nations) responded earlier and more effectively after the first signs of an uncharacteristic outbreak, it is likely that the number of lives lost, the impact on health infrastructure, and the magnitude of the eventual response could have been drastically diminished,” the paper says. “It is incumbent upon the global public health community to identify gaps revealed during the early stages of the epidemic so that we improve our collective ability to detect and respond early to the inevitable next emergency disease.”

The kind of local knowledge that’s available was epitomized by the finalists of the USAID Grand Challenge for Development, which targeted Ebola.

The ergonomic tent design that was submitted by Resilient Africa Network (RAN) and Makerere University was one of the three finalists in the competition.

The RAN led team will now receive some support and funding to further develop their idea, with a prototype hoping to be made available in the next few months.

The RAN led team will now receive some support and funding to further develop their idea, with a prototype hoping to be made available in the next few months.

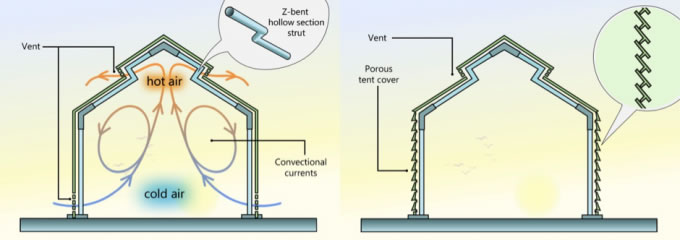

“The proposed next generation ergonomic tent is a modification of the traditional tent and maintains the current tent design in simplicity, affordability and structural stability. The new design offers a revolutionised mechanism for heat and air exchange in two ways: Creating a system for convectional currents using ambient air and creating porous walls that allow air exchange to cool the tent interior,” the creators say.

They’re confident that their design will revolutionize the working conditions of aid workers in areas such as the Ebola hotspots in west Africa.

“The tent is the super-structure that houses most of the operations of the Ebola Treatment Units (ETUs),” they say. “In the heat stressed environments of ETUs in tropical Africa, improved air-circulation in the tent structure will reduce average temperatures in the patient management and administration spaces, thereby positively impacting on the comfort of health workers.”

It’s a great example of how solutions can often emerge from local communities, without expertise having to be parachuted into environments that it is often ill-suited for. All it takes is the will to search out solutions locally.