Whilst most organizations these days regard innovation very highly, there remains a vast gap between research leaving academia and it becoming standard practice in the outside world. The size of this gap generally depends on the industry, but a good heuristic to go by is ten years.

In a world that’s changing as rapidly as our own is, that kind of diffusion is pretty poor, yet a recent study highlights just diffusion of research is a variable art.

Its authors set out to explore why it was that some research seemed to blaze a trail from the minute the ink was dry, whilst others labored away in obscurity for decades before then suddenly taking off.

The authors labeled this latter group as ‘sleeping beauties’, and they were the focus of the study. Can research really be ahead of its time?

“A ‘premature’ topic may fail to attract attention even when it is introduced by authors who have already established a strong scientific reputation,” the authors say.

The ‘sleepiest’ paper discovered by the study was from statistician Karl Pearson, who published his work in 1901, but it didn’t receive more widespread attention until 2002.

Interestingly, of the top 15 sleeping beauty papers, nearly 25 percent of them were published over 100 years ago.

“The potential application of some studies are simply unforeseen at the time,” the authors say. “The second-ranked sleeping beauty in our study, published in 1958, concerns the preparation of graphic oxide, which much later became a compound used to produce graphene, a material hundreds of time more resistant than steel and therefore of great interest to industry.”

The anatomy of a sleeping beauty

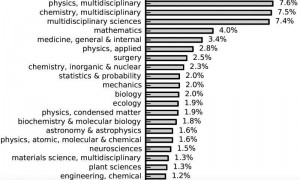

The study revealed that the subject area with the highest number of sleeping beauties was physics, followed by chemistry and mathematics. The most common journals for hosting such papers included Nature and Science.

The authors arrived at their finding after trawling through millions of publications over the course of the last century or so of academic research.

They determined the strength of dormancy by comparing the citation history of each paper with the year when it achieved its maximum number of citations.

The authors contend that the largest number of sleeping beauties occur in fields where a jump into a new discipline is made. For instance, academics may discover new resonances with the material in their own areas.

There appeared to be no other characteristic that made a paper a prime candidate for such status however, and of course it largely looks at papers published before open access and tools such as social media for promoting each paper.

It would be interesting, therefore, to see whether changes such as these have significantly changed the intellectual landscape and made it easier for papers to cross the chasm, or whether the fundamentals of certain papers being simply ahead of their time will remain true indefinitely.

I suspect most of the time it's the poor marketing capabilities of the researcher. It's a skillset that few seem to possess.

Probably true to a large extent Nick.

Interesting. Just goes to show how big an issue it is in disseminating research findings to a wider audience.