Earlier this year I covered the launch of a new paper from Andrew McAfee that explored the changing requirements for work.

Earlier this year I covered the launch of a new paper from Andrew McAfee that explored the changing requirements for work.

Whilst the paper doesn’t strictly speaking look at the future of work, it does nonetheless give us a valuable lesson into the changing nature of skills, and their value in the workplace.

The paper highlights the rapid pace of change and progress in a wide range of technologies. Therefore they urge people to take a flexible approach to learning and skills development, even if this means changing their occupation.

That was very much the tone taken in a second paper, published via Oxford University, that looked at the potential for technology to disrupt over 700 different occupations.

It suggested that digital technologies could provide a decent substitute for the jobs of some 140 million knowledge workers in the very near future.

So what can you do?

Whilst a university education remains important, it is increasingly the baseline and does little to distinguish you from anyone else.

Of course, one particular challenge is the changing nature of training and learning. Whilst there are an increasing array of opportunities to learn new skills in the digital age, we are also increasingly responsible for our own development.

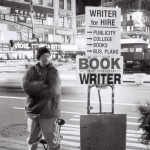

With more and more of us setting out on our own, the onus is very much on us to both find and finance our own learning and development. With organizations hiring in ready made talent for ‘gig’ type work, there is next to no incentive for them to train people up.

As much as we can gage about the future of work, it would seem likely that an adaptable skillset would be a basic requirement to cope with any changes in the work environment.

The question then becomes how proficient the growing freelance economy is at learning on the go and picking up the new skills required to make this adaption.

If they are proficient then it makes the labor market incredibly flexible. If they are not however, it renders vast swathes of the population somewhat stuck offering skills that are no longer needed.

Early signs

The early signs of, for instance, the MOOC student body are not particularly encouraging. There have been various studies that set out to explore just who is enrolling on courses.

Most suggest that those who enroll on the courses are those who already place a high value on learning, with teachers particularly enthusiastic.

There is often a tendency, such as with the recent McKinsey report on the so called ‘gig economy’, to look at things purely from the perspective of an organization, or from a macro economic perspective at least.

From that vantage point the appeal is obvious, both in terms of encouraging more people into the workforce whilst providing employers with a hugely flexible labor force.

It’s a largely unashamed cheerleader for the benefits of online labor marketplaces to improve economies around the world, but if we are to roll with the changes in the workforce, we’re more likely to succeed if we do so armed with both sides of the equation.