Over the past few years there have been any number of studies that have explored how information spreads throughout a network, and indeed what makes something go ‘viral’ in nature.

As much as there is any consensus on this, it seems as though there is no consensus at all, with no silver bullet appearing to emerge from the literature to describe with any certainty why some things spread and others don’t.

A recent study from researchers at the University of Southern California highlights how we are often tricked into thinking that something is much more popular than it actually is.

The social network illusion

At the heart of the illusion is the so called friendship paradox, whereby your friends, on average, will always have more friends than you, which is explained by those with a huge number distorting the average.

This phenomenon appears constantly in social networks, whether looking at how many connections you have, how often you’re cited, how much content you create and so on.

The paper notes that this can also distort our perceptions of popularity. For instance, a piece of content can be incredibly popular among our friends, but be altogether more rare in the wider network.

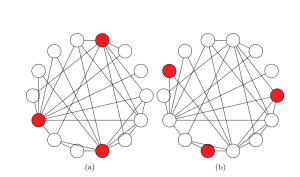

The authors illustrated this illusion with an example whereby 14 nodes formed a network. Three of the nodes were colored, and a count made of how many of the remaining 11 nodes can link to them in a single step (you can see an example below).

In the first example shown above, each uncolored node can see over half of their colored neighbors. In the second example however, this isn’t the case at all, and this is despite the structure being identical in both networks. The only change is the particular nodes that are colored.

In the first example shown above, each uncolored node can see over half of their colored neighbors. In the second example however, this isn’t the case at all, and this is despite the structure being identical in both networks. The only change is the particular nodes that are colored.

So why does this happen?

The authors explain that this occurs when the most popular nodes in the network are colored in. As these nodes tend to have the greatest number of connections to other nodes, they skew the average.

Does this occur very often in the real world? You’ll perhaps be unsurprised to know that it does, whether it’s in the academic world of citations, the social news world of Digg or even the blogosphere.

“The effect is largest in the political blogs network, where as many as 60%–70% of nodes will have a majority active neighbours, even when only 20% of the nodes are active,” the authors say.

Of course, this is interesting and relatively harmless for things like the latest ‘hit’ YouTube video, but there have also been numerous studies exploring the spread of misinformation throughout social networks, which has a rather more insidious effect.

Whilst the study is interesting, there still seems enough divergent opinion on just how things spread to say the jury is out. I’ll be covering another study on this topic tomorrow as a case in point.

It's not just on social media either is it? I'm sure if you surround yourself with a particular point of view then you kid yourself into thinking that perspective is much more common than it really is.

Exactly, a very similar phenomenon.

Social media has several advantages over professional journalism. Media is run by conservatives bent on consolidating power for themselves, not sharing important news. National focus misses local issues that affect individuals directly, not indirectly. Blogs are not frequent enough for spontaneous events, but do analyze issues better than tweets or posts, though tweets are interactive conversations that involve participants immediately, rather than stilted pontification that comes out of media. To garner "viral" means to pander effectively to masses, but, right, a lot has to do how a post gets repeated and staged by people on a network.

I agree with this completely. Spot on!

Nice research, thanks for sharing.

Interesting study

That's why it's vital to identify the key influencers and build connections with them.

Its why we need you guys… to explain this to us mere mortals !!

I wouldn't say that Susan 🙂