I wrote earlier this year about some of the ways that AI is helping us to do our jobs better. One of these is in more efficient route planning to help service personnel get to jobs faster.

I wrote earlier this year about some of the ways that AI is helping us to do our jobs better. One of these is in more efficient route planning to help service personnel get to jobs faster.

It’s the kind of travelling salesman problem that has been challenging people since the 1930s due to the computational difficulties involved.

Suffice to say, our computing power has advanced such that this kind of challenge is now very doable, hence why algorithms are being deployed instead of human route planners.

Learning from humans

There is still much that algorithms can learn from how humans devise the optimal route to get from A to B. A recent study, conducted by researchers from DeepMind and the University of Oxford, explored just how we do it.

“The idea is basically to understand how humans or animals make long-term decisions,” the researchers say. “We’re interested in trying to find machine-learning solutions to difficult tasks and real-life problems. Quite often it can be useful to draw inspiration from neuroscience.”

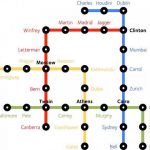

The team used a game based approach to try and delve into how our brain goes about making decisions. The game involved a virtual underground station, with each station representing a single step. The different lines then represented a step up the hierarchy.

In total, 22 people were trained to play the game, before then being given a target to try and reach whilst their brains were monitored in a fMRI scanner.

Deconstructing our brain

The team were particularly keen to explore whether participants were focusing on the line they would take or the stations they would go through.

When the data was analyzed, it emerged that brain activity (and response time) increased as the complexity of their route increased. Interestingly however, this only occurred when the complexity involved a number of line changes rather than the number of stations, which makes sense as it is only really changing lines that renders a route complex.

The brain activity that processed this kind of thinking took place in the dorsal portion of the medial prefrontal cortex, which is widely associated with high cognitive functions.

“We show, in a more straightforward and direct manner than previous studies, that there are hierarchical representations reflected in the brain,” the authors say.

Interestingly however, as participants got closer to their end goal, their ventromedial prefrontal cortex and hippocampus were triggered. This should come as no surprise as the hippocampus has been linked with the completion of goals for some time.

The team hope that this deeper understanding will go some way towards allowing them to develop smarter algorithms.

“We want to see how the human brain implements things like hierarchical structures in order to design more clever algorithms. In machine learning, having a hierarchical representation for decision making might be helpful or harmful depending on whether you choose the right hierarchy to implement in the first place,” the researchers conclude.