Each year INSEAD, WIPO and Cornell University produce the Global Innovation Index, which attempts to rank nations according to their innovation capabilities. The 2018 version has been released recently, with Switzerland continuing to dominate the index, as it has for the past 8 years.

Each year INSEAD, WIPO and Cornell University produce the Global Innovation Index, which attempts to rank nations according to their innovation capabilities. The 2018 version has been released recently, with Switzerland continuing to dominate the index, as it has for the past 8 years.

The presence of Switzerland at the top of the rankings underlines the relatively slow pace of change, with most of the top 10 in this years index consistent with previous editions.

As with previous years, each country is rated according to various criteria that the researchers believe underpin good innovation, including access to finance, a robust legal framework, excellent universities and high investment in R&D, and then the outputs of innovation, such as academic papers, patents and startups.

Perhaps most noticeable is the domination of European countries in the index, with 6 of the top 10 coming from Europe. This is despite longstanding challenges across the continent in transferring intellectual excellence into commercial success.

Supporting startups

One European country that does better than most is the UK, with a recent policy brief designed to further support and promote entrepreneurship in the UK. A recent roundtable discussion at the London School of Economics suggested that Britain is well placed to promote startups, especially compared to its European peers. Underpinning this success are liberalized markets, robust financial instruments, strong knowledge creation and a powerful intellectual policy framework.

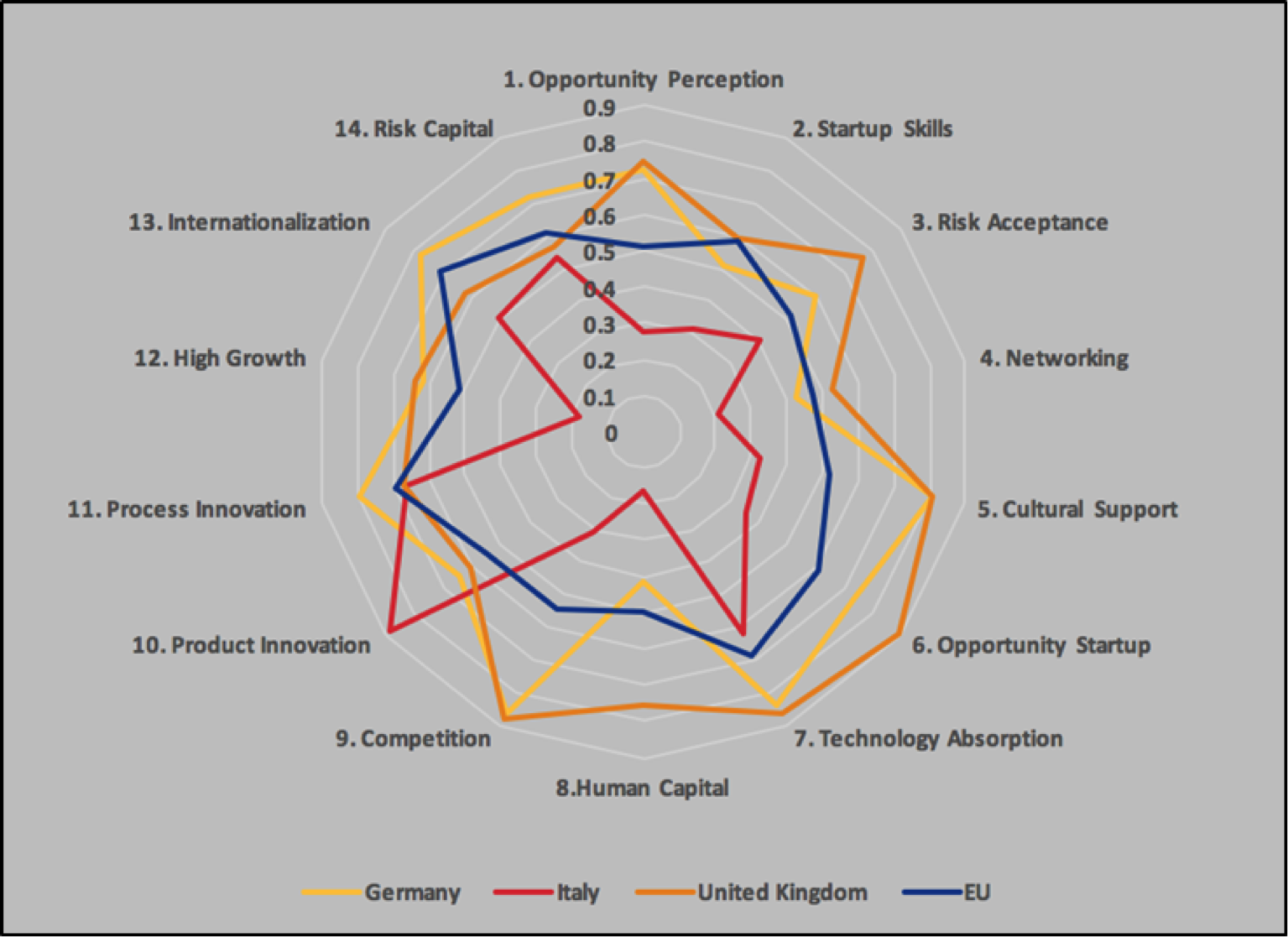

The attendees identified 14 pillars of entrepreneurship (outlined above), with the UK performing well on many of them relative to other EU nations. Nonetheless, it identifies a number of strengths and weaknesses. For instance, whilst opportunity recognition and risk acceptance are high, networking and basic startup skills are lower. There are also ongoing challenges involved in selling overseas that limit the potential of companies to reach scale.

The attendees identified 14 pillars of entrepreneurship (outlined above), with the UK performing well on many of them relative to other EU nations. Nonetheless, it identifies a number of strengths and weaknesses. For instance, whilst opportunity recognition and risk acceptance are high, networking and basic startup skills are lower. There are also ongoing challenges involved in selling overseas that limit the potential of companies to reach scale.

Central to the success of Britain’s startup scene is access to talent, with leading universities acting as a honeypot for smart people who then go on to build companies. The attendees believe however that insufficient effort is made to encourage people to stay in the UK, even aside from any regulatory issues that may arise as a result of Brexit.

They also believe that more needs to be done to support the scale-up of projects, with American startups much quicker to grow, and German startups having an obdurance that belies the relatively low number of startups in the country. What’s more, efforts are overwhelmingly concentrated in London and the South East, with London rivalling Silicon Valley as a startup hub. This concentration dilutes regional energy across the country however, and the attendees urge policy makers to address entrepreneurialism across the land.

Triggering discussions

Suffice to say, league tables like those produced by INSEAD are not without critics. Indeed, a group led by Charles Edquist of Lund University, has criticized a similar index produced by the European Commission as a wholly blunt instrument that massively over simplifies what is an inherently complex topic in order to produce one unified ‘innovation’ score for each country.

They argue that the equal weighting that the Commission assigns to each of their 27 sub-indicators is unrealistic. In reality each of the 27 measures different things and with varying degrees of importance to the innovation process. As such, in reality the index is best taken with a large pinch of salt rather than allowing a nation to laud (or bemoan) its efforts.

What such league tables do however is provoke discussions of the kind seen at LSE, and in that sense they can hopefully be a force for good.