I’ve written previously about research highlighting the value of travel for the productivity of academic researchers. 14 million research papers were analyzed from around 16 million researchers over a seven year period. Around 4% of those researchers could be regarded as ‘mobile’, in the sense that they regularly authored papers with teams in different countries. Those researchers typically had a 40% higher citation rate than their non-traveling peers.

Recently, RAND Europe set out to find who are the most well travelled researchers in the world. They surveyed a few thousand researchers from 109 countries for a recently published paper. The results revealed a very mobile workforce, with around 75% of respondents having moved to another country for work at some point in their career.

It emerged that senior researchers tend to travel more often, but all believed that visiting or moving to other countries benefited their research. These overseas experiences had given them new collaborations and support in developing ideas, skills and expertise.

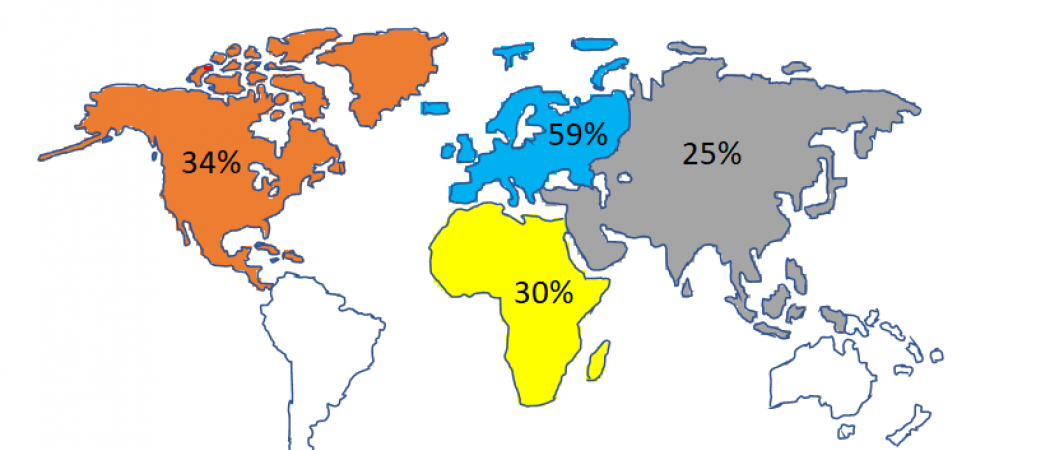

It was not all smooth sailing however, with a number of researchers citing challenges such as family responsibilities, access to funding and a general lack of information about opportunities abroad the the hurdles to jump through to secure them. These obstacles were especially high for researchers from Africa and Asia.

As the previous research highlighted however, it’s important that these barriers are overcome, as the efficiency, output and career progression of scientists is linked to their ability to move internationally.

To date, Europe has been the most mobile and connected research community, and its researchers have thrived as a result. There are concerns among researchers about the UK decision to leave the EU however, which coupled with the Trump administration in the US makes the open climate less certain.

“The international movement of researchers enables ideas to spread, collaborations to form and new perspectives to be gained,” the authors say. “The benefits of international movement are felt by all, but obstacles to movement are currently felt disproportionately by some.”

The authors believe a number of things can be implemented to improve the mobility of researchers, including:

- funding that is tailored to the specific needs of researchers in different regions;

- better information about research jobs overseas;

- greater support for obtaining visas;

- support in adapting to a new country; and

- more support in reducing the family burdens associated with the move

“Although there are clear benefits to international movement for researchers and research, it is important not to lose sight of the personal and practical challenges that this movement can present, from the hardship of moving to an unfamiliar place far from family and friends to the day-to-day challenges of dealing with bureaucracy in a new country and a foreign language,” the authors conclude. “Care needs to be taken when factoring movement into decisions around funding or promotion, as this factoring in could disadvantage some researchers based on their nationality, caring responsibilities or other factors which may inhibit their ability to move and travel.”