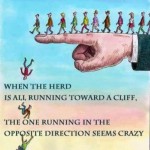

When we lose our collective marbles and follow the herd towards an incoherent conclusion the rationale is that things would have been fine had we only chosen to be smarter and thought about what we were doing rather than acting on impulse.

When we lose our collective marbles and follow the herd towards an incoherent conclusion the rationale is that things would have been fine had we only chosen to be smarter and thought about what we were doing rather than acting on impulse.

A recent study from UC Davis suggests that we don’t tend to follow the herd out of stupidity however, but rather out of innate tendency to act in a pack.

The research saw volunteers play a number of simple reasoning games, with the researchers monitoring their behavior. It found that behaving very similarly to your peers is a pretty standard scenario, regardless of the situation. What’s more, this happened even when individuals were deploying special reasoning processes that are designed to combat just that.

“The basic idea is that we have this preconception about fads and panics and flocks and herds, that they are driven by our basest animal spirits, and that adding thoughtfulness or education or intelligence would make those things go away,” the authors say. “This paper shows that people who are being thoughtful (specifically people who are doing dizzying ‘what you think I think you think I think’ reasoning) still get caught up in little flocks, in a way that the game they end up playing is driven less by what seems rational and more by what they think the others think they’re going to do.”

Group decision making

Each game in the study was designed to test a different mode of thinking, and therefore should have evoked a variety of reasoning methods in the players. Interestingly however, this didn’t happen, with the same herd like behavior emerging in every game.

In one game, called the Beauty Contest, players were given a reward whenever they guessed a number ranging from 0-100 that was closest to two-thirds of the average of all numbers submitted by the players. Another, called the Mod Game, asks players to choose a number between 1 and 24, with players earning more points by choosing a number that is one above another players. Each game was exposing supposedly big differences in our thought process, but the reality suggested something very different.

Whilst we associate herd like behavior as a bad thing, it can also be good as the group can work more effectively when their knowledge is combined. For instance, a peleton in a cycle race can move effectively around an object in the road that the vast majority of riders don’t see.

“These games show that sophisticated human reasoning processes may be just as likely to drive the complex, often pathological, social dynamics that we usually attribute to reactive, emotional, nondeliberative reasoning,” the researchers conclude. “In other words, human intelligence may as likely increase as decrease the complexity and unpredictability of social and economic outcomes.”