When you begin to regard ideas generated outside of your organisation as equal, if not superior, to those generated inside of the organisation, it can often require a shift in how the organisation is structured to reflect this new zeitgeist.

For instance, much of the 20th century saw companies aligned with the product very much at the centre, with operational units then organised across product, brand and geographical lines. In such a world, services are usually tacked onto the side, and very much take their lead from the product side of the business.

For a company that is seeking to move away from commoditized products towards co-created services, this is far from ideal. Achieving the ideal of customised solutions for customers delivered in an economic and efficient manner is a challenge many organisations struggle with.

To tackle this issue, some companies split themselves into customer facing front end units, that are then linked to standardised back ends. The customer facing units therefore package customised solutions for individual customers, thus both serving the customer well and delivering the kind of income that secures them organisational clout.

The back end part of the business then strives to deliver standardized services that can then be modified for each customer at a relatively low cost. The concept revolves around the provision of modular and reusable elements that can then be mixed and matched by the customer facing front end according to demand.

Such shifts in organisational structure are possible due to the lowering costs of communication and organisation offered by information technology. Economist Ronald Coarse believed that the firm itself came into being when transaction costs were such that it made sense to pool resources together into a single entitity, with the activities thus in question therefore conducted in-house.

Contingency theory proposes that there is no one correct way to design an organisation, but that instead, certain structures work more effectively given certain contextual factors.

The structure of your organisation has already been shown to effect how well we process information or communicate, with many academics also highlighting its impact on our ability to innovate.

Similarly studies have suggested that in order for external searches for knowledge to be effective, organisational support needs to be given to internalise that knowledge within the enterprise once it’s been found.

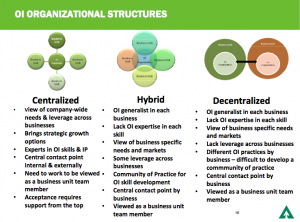

It has likewise been found that for open innovation to be truly successful, organisations should resist the urge to structure themselves according to product, technology or region. The optimal structure appears also to favour generalists rather than specialists, who can thus apply their skills widely, both in the search for external knowledge and it’s integration into the organisation.

Before embarking on the open innovation journey, it may well be therefore that you need to consider whether your organisation is structured in such a way as to fully capitalise on its possibilities. Research has particularly shown that two distinct areas of organisation structure need exploring:

- Formulation – organisations that have formal plans and procedures to internalise knowledge perform best with open innovation.

- Decentralisation – best performers are those organisations for whom control of open innovation is delegated down the organisation, with decentralisation especially helping the search for and integration of knowledge.

As Drucker might have said, we should no longer need convincing of the merits of looking outside our organisation for knowledge, it is merely how best to accomplish it.